Pf1zered! How Side Effects from the You-Know-What Took my Life Away, and How I Got it Back by Defying the Medical-Governmental Complex

Part II—Life and Health before Covid

I was brought up to trust the Medical-Governmental Complex. After all, my parents were part of that generation that came of age during World War 2, and emerged from the war with a glittering vision of the bold technological future that Big Science was going to bring. A future of jet travel, rocket ships, particle accelerators, computers, TV dinners, vaccines, interstate highways, Freudian analysis, scientific child rearing, and thalidomide. All powered by atomic energy. Sure, there was a risk that some of these technologies might be put in the service of evil. But fortunately, we had Big Government to protect us. All under the benign supervision of the war-hero president, Dwight David Eisenhower. My mother voted for him twice because his bald head and megawatt smile reminded her of her favorite uncle. Surely a favorite uncle would never let us down.

I don’t think anyone would accuse me of being unfair if I were to say that, while many aspects of this vision became reality, it was not without some downside.

This is the story of how Covid vaccine side effects took my life away, and how I got it back by defying the Medical-Governmental Complex (MGC). You can read it from the beginning starting here. In this installment I’m going to tell you a bit about my life and health before the pandemic, and how I first came to suspect that all was not well with the MGC. That shaped a lot of my attitudes during the pandemic itself.

But first a disclaimer: I’m not a physician. I’m not anything in the medical profession except a patient. I have no opinion whether what worked for me will work for anyone else, and nothing I say should be construed as advice. It’s just the story of what happened to me; make of it what you will.

As I said, when I was growing up we believed in doctors in our house. My parents had Dr. Spock Talks with Mothers, Anatomy of an Illness, The Denial of Death, and all the other latest medical bestsellers on their nightstands, next to bottles and bottles of Valium, Percocet, Fiorinal, Darvon, probably something for gout, and God knows what else. When they went on vacation, they needed a whole carry-on just for the pills.

My father in particular was a hypochondriac and ran to the doctor for every little ache and pain. One day he got a look at his medical chart, and the doctor’s comment next to nearly every visit read “Patient reassured.” Still, it seems to have paid off for him. He lived to the ripe old age of ninety-two.

We believed in psychiatry in our house too. When my grandfather died, my grandmother was so heartbroken that she spent half the year in bed with migraines. Off to the psychiatrist with her. That was actually successful, so much so that I was next. I never liked to be told what to do, and this often led to defiant outbursts of temper. My mom wanted the psychiatrist to fix me. That was less successful.

Of course my sisters and I got all the vaccinations. And at the least sign of a sniffle, we were rushed over to Dr. King’s office. We liked going to Dr. King’s office. It was a day off from school and if we were “lucky” enough to have strep, he prescribed the kind of penicillin that came in a yummy red liquid. And he was the spitting image of Mister Rogers. Same voice too. Surely Mister Rogers would never let us down.

Anyway, thanks to the pains that my parents took, or perhaps despite them, I grew up reasonably healthy. Not 100% though. I had to be very careful with colds or I’d be coughing for weeks, sometimes months, after my other symptoms cleared up. Also, like my grandmother, I suffered from migraines. Often they were stress-induced. I’m not sure how old I was when that started, but it was definitely very early. I remember one time my father had just installed the window air conditioners for the summer. This was a big deal for him. He grew up poor and air conditioning was a status symbol, a physical manifestation of his adult success. And again, the whole bold technological future thing. So he had them running full blast. And I had a migraine which made me extra sensitive to cold. I asked him to turn off the A/C. Hurt, he wanted to know why. But my language skills weren’t sufficiently developed to communicate what was wrong with me—I was that young. Not sure what a child that age had to be so stressed about, but anyway the air conditioning kept running. Later, by my early teens, I was already taking Fiorinal—a pretty serious drug for a kid. FFS, it’s a barbiturate. In the 1990s, when triptans came along, I tried those but they didn’t help. Oh, well, all the cool people have migraines. Caesar. Jefferson. Cindy Brady.

But most of all, I had to worry about my heart. The family history on my mother’s side wasn’t good. My grandfather was fifty-four when when he had his first heart attack, which he survived. He was a shoe buyer for Filene’s department store and after he got out of the hospital they moved him from women’s shoes to men’s. They said it was less stressful. Which didn’t prevent a second coronary, ten years later; that one tragically killed him. Still, he lived longer than any of his brothers. One of them, Abe, was forty-six when he died, leaving a sixteen year old daughter who had to quit school so she could go out and support her family. According to legend, my great grandmother was so distraught that, like Hamlet, she jumped in the grave. Another brother, Samuel, dropped dead at twenty-five.

And it looked like I didn’t fare any better in the genetics department than they did. Even in my twenties, I had high cholesterol. The Medical-Governmental Complex’s state-of-the-art antidote, in that pre-Statin age, was diet, specifically a diet high in grains, fruits, and vegetables, and low in meat, eggs, and dairy. Sweets were to be avoided, as were fats. If you had to eat the latter, polyunsaturated fats, the kind found in seed oils, were considered preferable to the saturated kind found in animal products. In 1992, these recommendations would be captured in the USDA’s infamous “Food Pyramid.”

I believed in the Food Pyramid. I really did. After all, it came from the medical experts who I respected so highly. Surely medical experts wouldn’t let us down. And besides, it made sense. If carrying extra body fat was linked to coronary artery disease, then obviously (or so I thought at the time) eating fat was bad. It followed that the foundation of our diet needed to be foods that were fat free or nearly so. So what else was there? Carbohydrates mostly. Which meant bread, cereal, rice, and pasta. I altered my diet accordingly. Breakfast was cold cereal (no milk) and a glass of orange juice. Lunch was frequently at the local Chinese buffet—rice in abundance, meat and vegetables in smaller quantities. I kept a box of pretzels in the office for an afternoon snack. Dinner was typically pasta (very easy for a single guy to make), or lean meats like skinless, boneless chicken breast. No matter how long I marinated it and how careful I was not to overcook it, the chicken was always tasteless and dry. Eating it was a chore, but with enough rice on the side I managed to get it down.

There was just one teeny problem with the Food Pyramid. It was bollocks. (Okay, I stole that line from Blackadder). It didn’t work. It didn’t work for me. And it didn’t work for America.

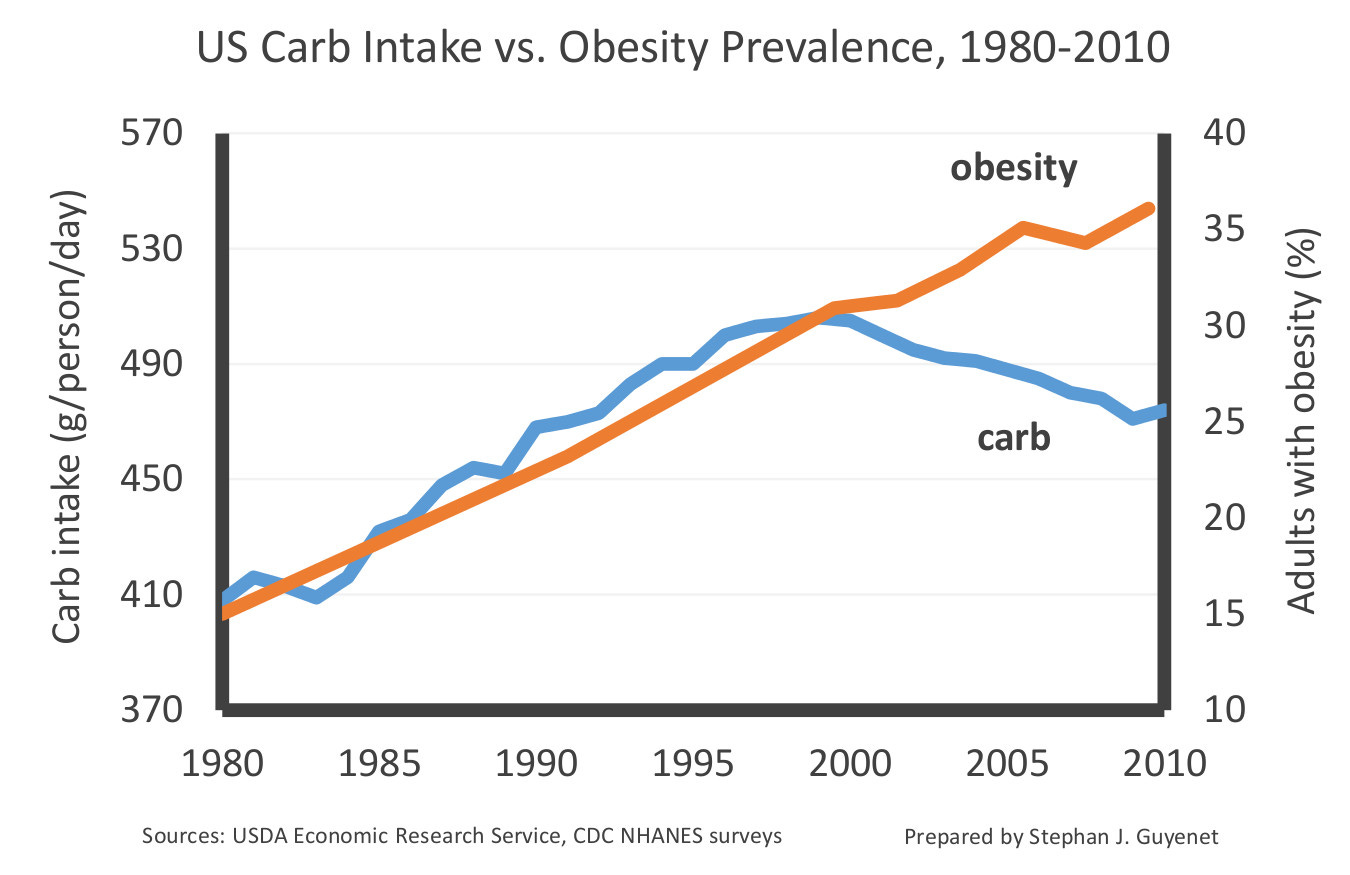

There is no doubt that the MGC high-carb recommendation in general and the Food Pyramid in particular coincided with an epidemic of obesity in the United States. It is less clear how much those recommendations contributed to it. Experts disagree.1 For one thing, the epidemic continued to grow even after carb consumption had dropped off.2 For another, it is not clear exactly how much people actually listened to those recommendations.

What we do know is that food processing companies, in a very incestuous and corrupt arrangement, try to influence USDA recommendations to favor their products. In turn, they are influenced by the recommendations in what they manufacture and how they advertise it. The most notorious example was Nabisco’s SnackWell cookies. Introduced the same year as the Food Pyramid, they were fat-free, in line with MGC recommendations (Granted, they were loaded with sugar, which was not in line with the recommendations; that kind of got overlooked). I remember talking with a woman in the supermarket who was puzzling over the label. “How can it be fat-free if the first ingredient is sugar?” she asked me. I explained that sugar and fat were completely different molecules. I was kind of a know-it-all about it (Ah, our younger selves). And while I was technically correct, in hindsight she was clearly right to be skeptical of this product. Too many people (including me), were not. The result was a phenomenon where consumers, convinced they were eating something healthy, ate more of it, and were worse off for it. The phenomenon even came to be called “The SnackWell Effect.”

And speaking of me, I was on the cusp of middle age, and despite what was supposed to be a good diet, my cholesterol was going the wrong way, as was my weight. Never excessively so—maybe an extra ten to fifteen pounds. Still, my coworkers noticed I had a tendency to stand with my arms folded over my stomach to hide the spare tire. And I liked wearing suits because the jacket and tie covered a multitude of sins.

Then something happened that shook the nutrition world to its foundations. The Atkins Diet became a thing.

Where the MGC said that fat is what made you fat and a high-carb diet was what you needed for cardiovascular health, Atkins said the opposite. Carbs are what makes you fat; don’t worry about dietary fat. He literally turned the Food Pyramid upside down. Instead of grain at the base, and meat near the top, to be eaten sparingly, now meat was the base, and fruits and grain, were not to be eaten at all, at least not in the initial “induction” phase.

None of this was new. Various high-protein, low-carb, “paleolithic” diets had been around for decades, and Atkins himself had written his first book on the subject in the 1970s. But in the late 1990s, the Atkins Diet suddenly went viral—perhaps as a reaction to the rising tide of obesity.

I first heard about Atkins from one of my coworkers and frankly, I thought he was trying to be funny. According to everything I “knew,” eating all the bacon you want couldn’t possibly cause you to lose weight. Or, as a critical article that I subsequently read put it, “Who ever heard of a diet where you can’t eat fruit?”

I soon learned it was no joke. And I did need to lose weight. I had some time off work at Christmas, and since everyone I knew happened to be traveling that year, it was an ideal opportunity to try a new diet, free from the complications of social life and work schedules that so often interfere with healthy eating.

In two weeks I dropped eleven pounds.

I was not alone. Whatever else one might say about the healthiness of the Atkins Diet—and it continues to be controversial—one thing was clear: millions of people lost a lot of weight.

And that was problematic. A diet which was the exact opposite of the Medical-Governmental Complex’s recommendations turned out to be good for me, and many, many others. That was not supposed to happen. It was my first clue that, not only was the MGC not the great font of wisdom that I had been brought up to believe, but that something was very, very wrong in the medical world.

Next up—The Pandemic Hits! Pf!zered Part 3—The Lies that Sold the Lockdowns

Bonus Post (Paid Subscribers Only)—More about diet and the MGC: Don't mess with my McNuggets: Why legacy McDonald's is healthier than "McPlant."

Michael Isenberg eats meat, drinks bourbon, and writes historical novels set in the medieval Muslim world. Please check out his latest, The Thread of Reason, at http://amazon.com/dp/0985329750.

“Did the Low-Fat Era Make Us Fat?,” PBS Frontline, last modified April 8, 2004, accessed February 10, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/diet/themes/lowfat.html.

“A Chemical Hunger – Part II: Current Theories of Obesity are Inadequate,” Slime Mold Time Mold, last modified July 11, 2021, accessed February 10, 2023, https://slimemoldtimemold.com/2021/07/11/a-chemical-hunger-part-ii-current-theories-of-obesity-are-inadequate/.