An Unlikely Candidate for Global Fame

The Murder of Mahsa Amini—One Year Later, Part 1

September 16 marked the one-year anniversary of the death of Mahsa Amini, the 22 year-old Kurdish woman who was murdered by Iran’s Morality Police because her hijab did not sufficiently cover her hair. It was a year of unprecedented demonstrations aimed at overthrowing the nation’s theocracy. In this article, I’ll discuss who was Mahsa Amini, her tragic death, and the protest movement that ensued. I’ll then cover the regime’s brutal response and what the future holds in a follow-up.

Who was Mahsa Amini?

If Ms. Amini in death became a global icon, the young woman with brown eyes and long dark hair was also a daughter, a sister, a niece and a favorite granddaughter. In recent interviews, Ms. Amini’s father, an uncle, two cousins and a family friend described her as an unlikely candidate for global fame, a person whose story has resonated so widely and deeply precisely because she could be any girl living and walking the streets of Iran.1

Her uncle described her as “an innocent and ordinary young woman.” Born in the city of Saghez in the dusty, brown Zagros Mountains, her parents, Amjad Amini, a government employee, and Mozhgan Eftekhari, a stay-at-home mom, named her Jina—Kurdish for “eternal”—and this is the name by which she was known to those who knew and loved her. But because Kurds are sometimes discriminated against in Iran, she was given a Persian name for the benefit of the outside world: Mahsa.2

By all accounts, Mahsa was quiet and shy. She had few friends but was close to her family. According to The New York Times,

Her favorite thing to do was to hang out and play with all the babies and children in the family,” said her 27-year-old cousin in a telephone interview from Saghez, Iran, who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution. If there was one place she emerged from her shell it was at weddings, her cousins and uncle said, where she wore long colorful Kurdish dresses, curled her hair and danced hand-in-hand with her relatives.3

In 2018, she graduated from Taleghani Girls High School, but was uncertain what she wanted to do with her life. She toyed with the ideas of doctor, pharmacist, actor, and radio host, while working at a dress shop owned by her father, now retired. After struggling to pass the entrance examinations, and then having to wait for an opening, Amini was finally accepted into the microbiology program at Azad University, where she was due to begin on September 23, 2022, two days after her twenty-third birthday.4

Such were the life and possibilities that were snuffed out by the theocracy.

The Murder

Lit up at night, Tehran’s Tabiat Bridge is spectacular to behold. Almost the length of three football fields, with three levels, the award-winning pedestrian overpass crosses over the Modares Highway, connecting the parks on either side. It features kiosks, restaurants, seating areas, plant life, and a view of the Alborz Mountains. Just the destination for young Iranians out on the town to gather as dusk approached on a warm, late-summer evening.

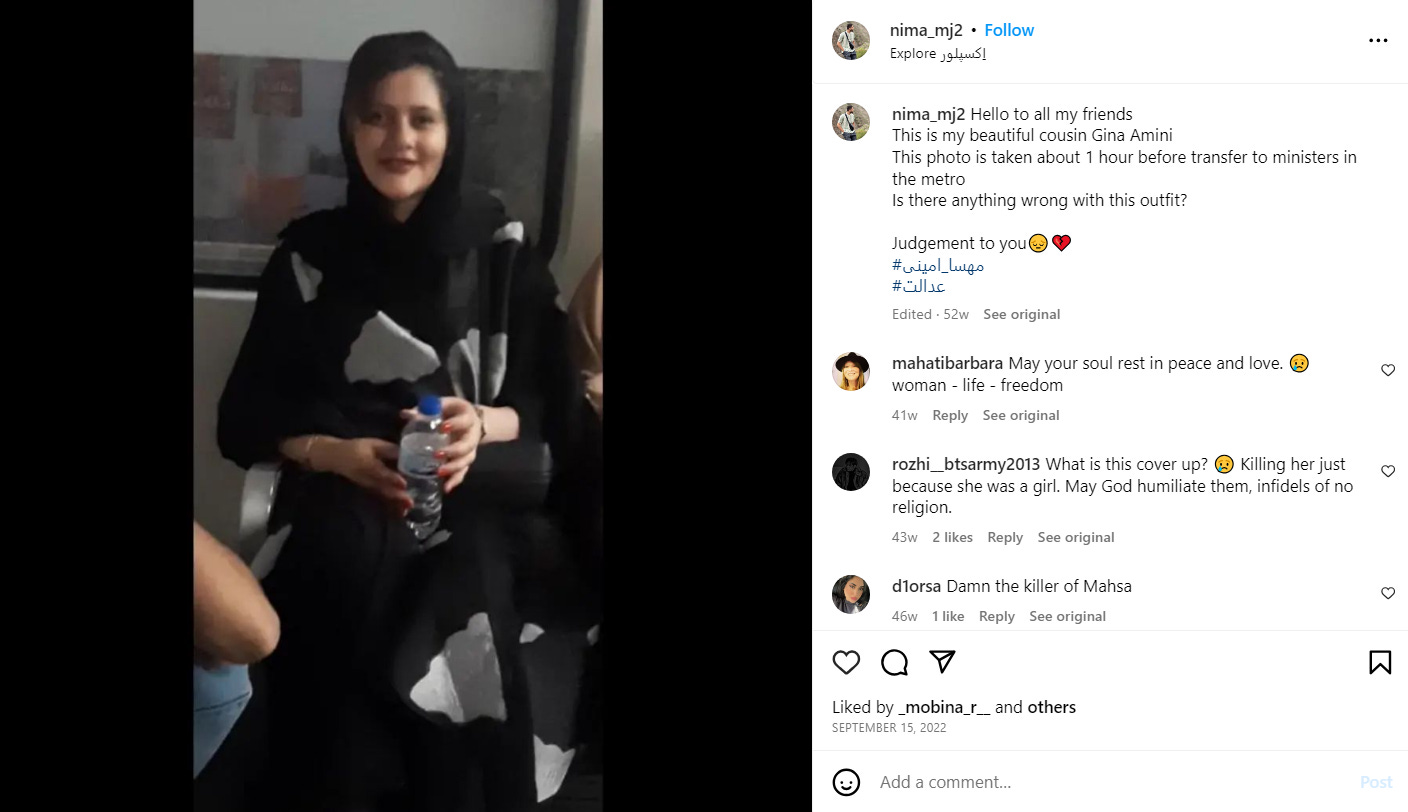

That’s where Mahsa Amini, her brother Kiarash, and two cousins were headed on Tuesday, September 13. The family had taken a vacation prior to Amini’s enrollment at Azad. They had spent some time in a resort town on the Caspian Sea, and then traveled on to Tehran to visit relatives. On the afternoon in question, the younger members of the family set out on an excursion of their own. They went by subway, where one of them snapped a photo of Amini. It showed her with a hijab covering her head and wrapped in a long black and white coat. “Is there anything wrong with this outfit?” a cousin would later ask on Instagram.

They emerged from the subway at the Haqqani Station, near the bridge. It was there that Mahsa Amini and the two cousins were confronted by the the Morality Police for allegedly violating the Islamic Republic’s edicts on appropriate dress for women. Mahsa was arrested. Kiarash implored the police not to take his sister; they beat him. “His clothes were ripped off,” their father said.5 Mahsa was forced into a police van for transport to a detention center where she would undergo “explanation and instruction.”6

There are two versions of what happened after that.

The official version, from the state mouthpiece, the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), was that after arriving at the detention center, “Amini suffered a heart attack and was immediately taken to a hospital, where she died on Friday. Police have rejected the reports saying that Amini was beaten and has said that no physical contact has happened between officers and Amini.”7 The IRNA statement was accompanied by security footage of a woman said to be Amini suddenly collapsing in what appears to be a classroom.

The director general of forensic medicine of Tehran province, Mehdi Faruzesh, repeated the claim that Amini had not been beaten. “No signs of injuries to the head and face, no bruises around the eyes, or fractures at the base of Mahsa Amini's skull have been observed,” he said.8

Some weeks later, a coroner’s report was released. It gave the cause of death as cerebral hypoxia caused by a pre-existing condition: it claimed Amini had been operated on for a brain tumor when she was eight.9 In an interview with Der Spiegel, her grandfather, Rahman Aili, stated that Mahsa had in fact had a benign brain tumor removed when she was a child.10

Mahsa’s father disputes this. “They are lying," he said. "She has not been to any hospital at all in the past 22 years, other than for a few cold-related sicknesses. She never had any medical conditions, she never had surgery.” Two of Mahsa’s classmates, who spoke to the BBC, said they had no memory of her ever having been in the hospital.11

The family and independent journalists give a very different version of the events of September 13: Eyewitnesses told Kiarash that Mahsa was beaten both in the police van and at the detention center, including blows to the head. A photo taken of her in the hospital, where she never regained consciousness, appears to show blood on her right ear.12 CT scans, reputed to be Amini’s, and leaked to Iran International by a “hacktivist group,” show a fracture to the skull, also on the right side.13

Amjad asked to see the body-cam video from the arresting officers. “They told me the cameras were out of battery," he said. Further, he was not permitted to see his daughter’s body after her death, until it was wrapped for burial, concealing signs of injury. Only her face and feet were visible—and there were bruises on her feet.

The shifting story about the cause of death, the delay in the release of the autopsy report, the absence of body-cam video, the wrapped body—it all screams cover up.

Mahsa Amini was beaten to death by her government.

The Demonstrations

The outrage over the arrest and beating of Mahsa Amini began even as she lingered in the hospital, and, this being the 21st century, it started on social media. “This is the brutality of Islamic Republic of Iran that has a seat at UN to monitor women’s rights globally,” journalist and activist Masih Alinejad tweeted on Wednesday the fourteenth.14 “Sickening,” wrote actor and human rights campaigner, Nazanin Boniadi. “How many innocent young lives must be brutally robbed before we all rise?”15 By the fifteenth, the infamous photos of Amini in her hospital bed began to circulate amid replies of “Horrifying,”16 “They are cowards beating a woman,”17 and “This is something I find difficult to believe is actually happening in the 21st century. This is disgusting on the part of the Iranian government. Shame on them.💔💔”18 A photo of Amini’s father and grandmother, tearfully embracing in a hospital corridor, was posted on Twitter by Niloofar Hamedi of The Daily Shargh (East) on Friday, and quickly went viral.19

When news of Amini’s death broke shortly after, protesters immediately took the streets. A group of demonstrators were captured on video marching through Tehran and chanting, “Death to the dictator!,” a reference to the country’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. From the beginning, the protests went beyond demanding reform to the dress code forced on women, and the vicious excesses of the morality police, and took aim at the highest level of government itself. The protesters faces were not shown, to protect them and their families from reprisals by the regime; only the lower halves of their bodies appear.20 Indeed this would become a regular feature of protest videos during the months ahead: demonstrators shown from the waist down, or from the back, or out of focus.

Amini was buried in Saghez the following day, Saturday the 17th. After the funeral, a much bigger, and much angrier crowd demonstrated in that city. Men shouted “Killing for a scarf. How long will the dust be on the head?”21 Women ripped off their hijabs, waved them in the air, and joined the men in chanting “Death to the dictator!”22

By Sunday the protests had spread to Sanandaj, the second largest Kurdish city in Iran, and Tehran University in the capital. IranWire reported it was “the first time a demonstration has been staged by students in a decade.”

A group marched down the street chanting the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” and carried placards bearing the message, in both Persian and Kurdish, “I don’t want to die”. One read: "Dear Mahsa, you didn't die! Your name will become a symbol".

At one stage, a group of paramilitary Basij members attacked the students. They in turn chanted “Shameless, Shameless".23

But these were just a few wisps of steam. By Tuesday—one week after Amini’s arrest—the volcano of protest was in full blown eruption. Demonstrations had spread to the majority of Iran’s 31 provinces. In Qazvin, protesters chased away a police car. In Sari, they scaled a municipal building and ripped down images of Khamenei, and of the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.24

Videos of huge crowds waving placards and chanting anti-government slogans continued to flood cyberspace on a nearly daily basis through the end of the year. October 26 in particular saw massive turnouts, as The New York Times explains:

By evening, demonstrations had spread across the country to many cities and university campuses, with large crowds in the streets clapping and defiantly chanting the mantras of the protests: “Women, Life, Freedom” and “We will fight and take Iran back,” according to videos on social media.

In the capital, Tehran, women tossed their head scarves onto bonfires in the street, shouting “Freedom! Freedom!” videos showed. In many places, the protesters condemned the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and chanted for his death and removal…

Earlier in the day, thousands of Iranians made their way to the northwestern city of Saghez, the hometown of Ms. Amini, to mark 40 days of mourning since her death in police custody, according to local media, rights groups and videos on social media. They came by car and motorbike or on foot, despite a heavy security presence in the city and threats of imprisonment and death from the authorities.25

One image from that day became iconic: a young woman standing on the roof of a car, her back to the camera, her long hair uncovered and flowing defiantly down her back, her arms raised in a gesture toward the thousands of mourners streaming toward Amini’s grave.

It was one of many acts of rebellion and bravery by individual protesters that autumn:

Women without hijabs became a common sight on the streets and subways of Tehran—and they fought back, verbally and sometimes physically, against anyone who tried to “correct”them.26

While western teenagers were videoing themselves undergoing various TikTok challenges—the “blackout challenge,” the “one-chip challenge,” and the “skull-crusher challenge” were especially popular at the time—Iranian teens came up with a video challenge of their own: they ran up to clerics and knocked the turbans of off their heads.27

When the national soccer team lost to the United States in the World Cup, throngs of Iranians honked their horns, cheered, and danced in celebration CNN quoted an anonymous celebrant in an unnamed Kurdish city as saying, “I am happy, this is the government losing to the people.”28

Schoolgirls replaced the pictures of Khamenei and Khomenei in their classrooms with “Woman, Life, Freedom” placards.29 Others chanted the slogan, along with a few choice epithets directed at the clerics, as they walked out of school entirely.30

In university dining halls, men and women started eating together, flaunting the gender segregation rules.31

These weren’t the first protests to rock Iran in recent years. In the 2009 Green Movement, demonstrators took to the streets to protest a disputed presidential election. Renewed protests broke out in 2017, when US President Donald Trump withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear agreement. The resulting “maximum pressure” policy of renewed economic sanctions threw the Iranian economy into a tailspin. Throughout the following years, there were numerous demonstrations against high unemployment, low wages, soaring food and gasoline prices, and shortages of water.

While all these protests were ultimately quashed by the regime, supporters had reason to believe that the Mahsa Amini movement would be different. The protests were aimed at the regime itself, rather than narrower issues like elections or the cost of living. They were more broadly-based demographically and geographically. And this time women were in the the vanguard—along with a new generation of student activists.32

The young protesters were unlike their parents. Raised on social media, they knew what life was like outside Iran—and that a better life was possible. As one video blogger, 16 year-old Sarina Esmailzadeh, put it, “We ask ourselves why aren't we having fun like the young people in New York and Los Angeles?”33

Older activists were stunned by their courage. One 51 year-old woman talked about being arrested at a demonstration. “They put me on the ground, and an officer put his boot on my back,” she told the BBC. “He kicked me in my stomach, tied my hands, picked me from my arms, and then pushed me into a van.” But then something amazing happened. “There were other girls with me in the van, but they were much younger. When I saw them and their bravery, I gathered myself. They started helping me. They were shouting and making fun of the officers. This generation is different from my generation. They are fearless.”34

The protester’s fearlessness seemed to be making its mark. By the end of year, the country’s prosecutor general, Mohammad Jafar Montazeri, was reported to have said that the parliament and the courts were “working and studying the issue of hijab.” A few days later, he added that the morality police “has no connection with the judiciary and was shut down by the same place that it had been launched from in the past.”35

Encouraging news, but activists were skeptical. As journalist Masih Alinejad tweeted, “It’s disinformation that Islamic Republic of Iran has abolished it’s morality police. It’s a tactic to stop the uprising.”36

Her skepticism was well-founded. The regime, whose response had already been drenched in blood, was just getting started in its efforts to discredit the protesters, stage counter-protests, and break up demonstrations by brute force. I relate the theocracy’s whole despicable course of action in my next installment.

Michael Isenberg likes ribeyes, bourbon, and writing novels about Persia. Please check out his latest, The Thread of Reason, at http://amazon.com/dp/0985329750.

Fassihi, Farnaz, “An Innocent and Ordinary Young Woman,” The New York Times, updated September 17, 2023, downloaded September 17, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/16/world/middleeast/mahsa-amini-iran-protests-hijab-profile.html.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Neufeld, Dialika, “Who Was Jina Mahsa Amini?,” Der Spiegel, December 8, 2022, downloaded September 18, 2023, https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/an-iranian-icon-who-was-jina-mahsa-amini-a-f6399d1e-589f-436e-8408-3c44861ba035.

“Iran: Mahsa Amini's father accuses authorities of a cover-up,” BBC, September 22, 2022, downloaded September 25, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-62998231.

“Iranian woman in coma after morality police arrest: activists,” France24, updated September 15, 2022, downloaded September 18, 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220915-iranian-woman-in-coma-after-morality-police-arrest-activists.

“Iranian police releases footage of young woman died after arrest,” IRNA, September 17, 2022, downloaded September 18, 2023, https://en.irna.ir/news/84889658/Iranian-police-releases-footage-of-young-woman-died-after-arrest.

BBC, September 22, 2022, op. cit.

“Iranian coroner disputes that Mahsa Amini died of blows to head and limbs, as protests continue,” Thomson Reuters via CBC, updated October 10, 2022, downloaded September 18, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/iran-mahsa-amini-coroner-report-1.6609470.

Neufeld, op. cit.

BBC, September 22, 2022, op. cit.

Neufeld, op. cit.

“Mahsa Amini’s CT Scan Shows Skull Fractures Caused By Severe Blows,” Iran International, September 19, 2022, archived September 20, 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20220920112159/https://www.iranintl.com/en/202209195410.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, September 14, 2022, downloaded September 25, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1570104003022950401.

Boniadi, Nazani, Twitter, September 14, 2022, downloaded September 25, 2023, https://twitter.com/NazaninBoniadi/status/1570183706882473984.

Keenly Aware, Twitter, September 15, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/keenfamily/status/1570507619097513984.

cblin, Twitter, September 15, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/Cblinn3/status/1570587665602609153.

Yinn James, Twitter, September 16, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/JamesYinn/status/1570714745703133184.

Hamedi, Niloofar, Twitter, September 16, 2022, archived September 19, 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20220919060253/https://twitter.com/NiloofarHamedi/.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, September 17, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1571078197583937536.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, September 17, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1571089237294067712.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, September 17, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1571134616974790656.

“Protests Continue in Tehran and Kurdistan Amid Fury Over Death of Mahsa Amini,” IranWire, September 18, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://iranwire.com/en/provinces/107630-protests-continue-in-tehran-and-kurdistan-amid-anger-over-death-of-mahsa-amini/.

“Iran Protests Against Woman’s Death in Hijab Case Spread to 16 Provinces,” VOA, September 20, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/iran-protests-against-woman-s-death-in-hijab-case-spread-to-16-provinces-/6756363.html.

Fassihi, Farnaz & Engelbrecht, Cora, “Tens of Thousands in Iran Mourn Mahsa Amini, Whose Death Set Off Protests,” The New York Times, Updated October 27, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/26/world/middleeast/iran-protests-40-days.html.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, downloaded October 3, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1592560664228552705,

https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1601611616860397568.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, downloaded September 26, 2023,

https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1608157776777302018,

https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1607448276156006400,

https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1596881135656894466.

Picheta, Rob et al., “Iranian protesters celebrate World Cup defeat, as fears surround players’ return,” updated November 30, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2022/11/30/middleeast/iran-protests-world-cup-defeat-celebrations-intl/index.html; Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, November 29, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1597725204335456257.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, November 16, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1593048216831856640.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, November 29, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1597599195514519556.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, October 27, 2022, downloaded September 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1585484931089588224.

Rojhelati, Ziryan, “The Demonstrations for Mahsa Amini: A Turning Point in Iran,” Washington Institute, October 7, 2022, downloaded October 3, 2023, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/demonstrations-mahsa-amini-turning-point-iran.

Ghobadi Parham, “Iran protests: Iran's Gen Z 'realise life can be lived differently,'” BBC, October 14, 2022, downloaded October 3, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-63213745.

“Iran protester: 'They said if we didn't keep quiet, they would rape us,'” BBC, September 27, 2022, downloaded October 3, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-63047372.

Montamedi, Maziar, “Iran prosecutor general signals ‘morality police’ suspended,” Al-Jazeera, December 4, 2022, downloaded October 3, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/4/iran-prosecutor-general-signals-morality-police-suspended.

Alinejad, Masih, Twitter, December 4, 2022, downloaded October 3, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1599393507503841280.