I saw the bullets in her body.

Woman, Life, Freedom—One Year Later. Part 2: The Islamic Republic's Brutal Response.

Warning: Contains accounts of violence, including sexual violence, which may be disturbing to some readers, and should be disturbing to all.

In my previous post in this series, I quoted 16-year old Sarina Esmailzadeh, one of thousands of teenage girls taking part in the Woman, Life, Freedom protests in Iran. “We ask ourselves why aren't we having fun like the young people in New York and Los Angeles?” she said.

On September 23 of last year, Sarina went to a demonstration in the city of Karaj, near Tehran.

She never came home.

According to Amnesty International, security forces used batons to beat her to death with blows to head.1

According to Iranian authorities, this teenager, who Iran International described as a “happy, intelligent, social-media savvy young girl,” committed suicide by jumping off a building.2

I trust Amnesty on this one.

Sarina was just one of hundreds of demonstrators, many of them women and children, who were slaughtered by the Iran regime in the wake of the death of Mahsa Amini.

This is the second installment in my series looking back at Amini’s death one year later, and how it sparked a massive campaign of protest and civil disobedience aimed at toppling the Islamic Republic of Iran.

In the first installment, I wrote about Amini herself, her September 16, 2022 death at the hands of the Islamic Republic’s so-called “Morality Police” for not wearing her hijab “properly,” the attempts by the regime to cover up the murder, and the protests that ensued. In this post I’ll discuss the regime’s response.

Part of that response was to wage a propaganda war. Government officials sought to discredit the demonstrators with tired, old accusations that they were puppets of the usual suspects. For example, a couple weeks into the protests, the dictator Ayatollah Ali Khamenei told a class of police cadets, “This rioting was planned. These riots and insecurities were designed by America and the Zionist regime.”3 Counterrallies were staged in Tehran and other cities where pro-government stooges chanted slogans attacking Israel and the United States.

Since these ploys fooled no one, other aspects of the regime’s response were far more vicious. A leaked document from the General Headquarters of Armed Forces, dated September 21 and obtained by Amnesty, ordered military commanders in every Iranian province to “severely confront” “troublemakers and anti-revolutionaries.” A second document, dated two days later, from a provincial commander in Mazandaran, elaborated on what “severely confronts” means: “going as far as causing deaths.”4

This regime didn’t waste any time putting this murderous policy into effect.

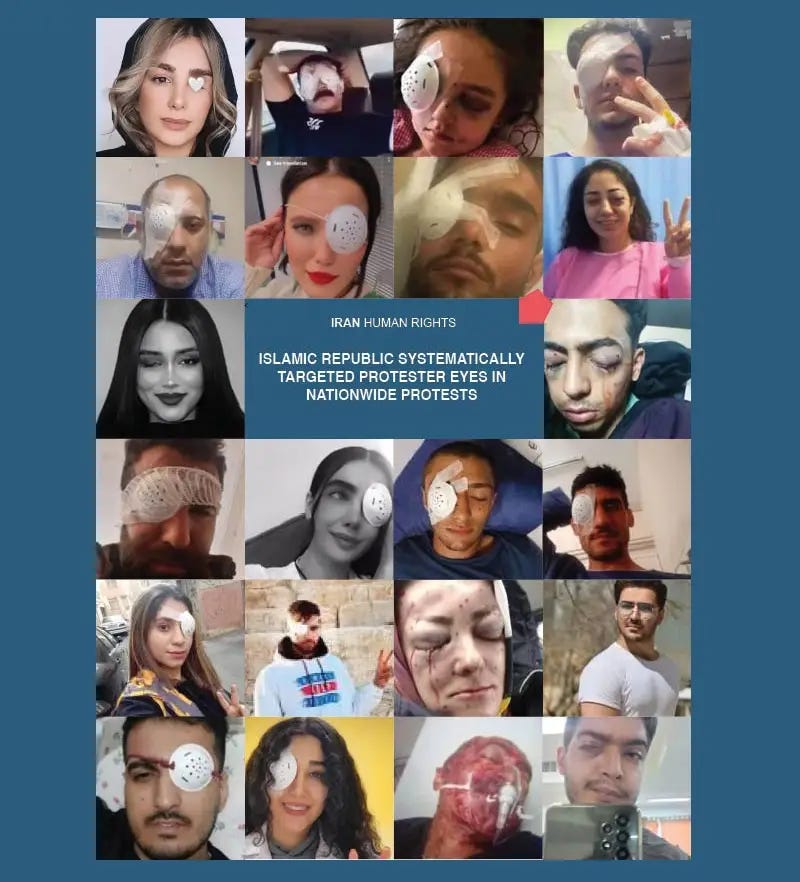

Demonstrations were broken up by brute force. Agents of the Basij, the paramilitary wing of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, charged into the crowds on motorcycles.5 Apparently unable to find sufficient number of Iranians willing to turn against their own people, the regime bolstered Basij forces by importing foreign fighters from its client militias in Iraq, Lebanon, and possibly the Palestinian territories.6 In addition to beating protesters with batons, as they did to Sarina Esmailzadeh, regime thugs fired on the crowds with live ammunition. The shotgun was a favorite weapon, and a particularly vile one for crowd control. Unlike a rifle, which can be aimed at an individual target with some precision, a shotgun scatters birdshot into the assembled masses, wounding violent troublemakers, peaceful protesters, and mere bystanders indiscriminately. Eyes are especially vulnerable to birdshot.

One of the injured was 32 year old Mohammad Farzi, a martial artist and street performer who goes by the handle “The Joker of Tehran.”

Less than a week into the demonstrations, Farzi was shot while attempting to assist a woman who was being taken away by authorities. X-Rays he posted on Instagram showed five shotgun pellets in his body, including one in his right eye. Although the prognosis to save the eye is good, he has lost 80% of his sight on that side and, as of August, had undergone three operations and was still being treated. “I’m proud that this happened to my eye for the sake of Iranian people,” he said.7

Others were less fortunate. Many lost eyes entirely. Although government sources denied it, witnesses stated that many of these injuries were not merely the result of random birdshot scatter; security forces deliberately aimed for faces and shot at close range with birdshot, paintballs, and rubber bullets.8

The New York Times reported that five hundred people sought treatment in Tehran hospitals for eye injuries during the first two months of protests, and another eighty in Kurdistan—and that doesn’t include the many who went untreated due to fears of reprisals from the Basij.9

The injured remain defiant. Ph.D. candidate Elahe Tavokolian, who lost an eye after being shot at a demonstration near Mashhad, is determined to see security forces tried for war crimes. She vows that someday she will “exhibit the bullet in an international court.”

Tragically, many victims are beyond defiance. Among them was Hadis Najafi, age 22. According to her sister, after Amini’s death, Hadis “cried for Mahsa for days, and that’s why she protested.” Two days before the death of Sarina Esmailzadeh, and in the same city, Hadis left her job for the day—she worked as a cashier in a restaurant—and headed out to a demonstration. As she walked along a darkened street, she recorded a TikTok video. “I hope in a few years when I look back,” she said, “I will be happy that everything has changed for the better.”10 About an hour later,11 she was shot and killed by security forces.12 Over 20 shotgun pellets penetrated her face, neck, chest, and abdomen.13

As with Sarina, and Mahsa herself, the Islamic Republic attempted to cover up Hadis’s murder. Authorities refused to release the body for two days, using it as leverage to try to get her father to agree to say that she had died of natural causes: a heart attack or a stroke.14 And after her father refused and Hadis’s corpse was finally turned over to the family, security agents showed up at the funeral,15 presumably to intimidate anyone inclined to use the occasion to speak against the regime.

Hadis’s grieving family sent a video to journalist and activist Masih Alinejad, which included footage of her twirling happily on a beach, her last TikTok message, her blood-soaked corpse and backpack, and statements from her mother and sister. “I see my daughter everywhere,” her mom says angrily. “Can’t eat or sleep. I saw the bullets in her body. All the ones dead and Mahsa are like my kids too.”16 She was particularly fixated on the fact that Hadis was in such a hurry to get to the demonstration that she skipped dinner that night. Just a random detail of the sort people share when they’re in mourning? An illustration of Hadis’s dedication to Woman, Life, Freedom? Or did her mother feel guilty that she hadn’t fed her child, not knowing she would never have an opportunity to do so again? One can only speculate. What I do know is there’s nothing for her to feel guilty about. All the guilt belongs to the Islamic Republic, whose hoodlums pulled the trigger.

Watching the video, one feels for Hadis’s mother. Now imagine the tragedy repeated hundreds of times, with hundreds of other protesters having their hopes and dreams cut short, and hundreds of other mothers mourning them. Iran Human Rights reports that, in the year since Amini’s death, at least 551 protesters were massacred by the regime, including sixty-eight children and forty-nine women.17

Thousands more were arrested. The Human Rights Activists News Agency puts the number of detainees, through January 5, at 19,262.18 Because the regime was eager to silence influential people who supported the protests, numerous prominent individuals from the worlds of media, sports, and entertainment were among the detainees. These included award-winning film star Katayoun Riahi,19 soccer star Voria Ghafouri,20 and journalist Niloofar Hamedi, who you may recall from Part 1: she was the source of a viral photo of Mahsa’s father and grandmother, tearfully embracing in a hospital corridor.21

Arrests were violent and treatment of prisoners harsh. One woman, Maryam (not her real name), told the BBC her experiences:

“They put me on the ground, and an officer put his boot on my back. He kicked me in my stomach, tied my hands, picked me from my arms, and then pushed me into a van.”

“I heard one of their commanders ordering their soldiers to be ruthless. The female officers are [just] as horrible. One of them slapped me and called me an Israeli spy and a prostitute.”

“We were moved to a small police station. They were not ready to receive so many people. They put at least 60 women, including me, in a small room. We were standing next to each other and couldn't sit or move.

"They said we could not use the bathroom, and that if we got hungry we could eat our stools.

"After almost a day, when we shouted and protested inside the room, they started threatening us that if we didn't keep quiet, they would rape us."22

The threats of rape were not idle.

Before Armita Abbasi, 20, became involved in Woman, Life, Freedom, she liked to post videos on TikTok of herself with her cats.

Arrested on October 10, she was hustled to Tehran’s Imam Ali hospital seven days later by plainclothes police. According to internal hospital staff communications, leaked to CNN, “she was hemorrhaging from her rectum…due to repeated rape.” One doctor said, “She was my patient. I went to her bedside. They had shaved her hair [to humiliate her] and her head was wrapped. She was scared and was trembling.” Once again, the regime tried to cover up its atrocities. The plainclothes men insisted that doctors write in their report that rape occurred prior to arrest. This was a lie; recall that she had been in custody for a week. “After the truth became obvious to all, they changed the whole script,” a staffer wrote. A government statement attributed Armita’s hospital visit to “digestive problems,” a diagnosis not consistent with her symptoms.23

Abbasi’s case was not isolated. Earlier this month, Amnesty released a 120-page report, “They violently raped me”: Sexual violence weaponized to crush Iran’s “Woman Life Freedom” uprising. It recounts the testimony of forty-five protesters who were sexually abused by security forces. Their experiences are horrific. Sensitive readers may want to skip the following quote:

Of the 45 survivors whose cases Amnesty International documented in detail, 16 were raped and 29 were subjected to other forms of sexual violence. The rape survivors included six women, seven men, a 14-yearold girl, and two boys aged 16 and 17. Six of the 16 rape survivors – four women and two men – were subjected to gang rapes by up to 10 male state agents.

State agents raped women and girls vaginally, anally and orally, while men and boys were raped anally. Survivors were raped with wooden and metal batons, glass bottles, hosepipes, and/or the sexual organs and fingers of agents. Eight survivors were raped in detention facilities belonging to the Revolutionary Guards; four in vans belonging to the security forces…one in what appeared to the survivor to be a school or preschool unofficially and unlawfully repurposed as a makeshift detention place; one in a residential building near a Basij base; and two in unidentified buildings.

The other 29 survivors were subjected to forms of sexual violence other than rape. In the cases of women and girls, these routinely included male security and intelligence agents putting their hands under their clothing and into their underwear; grabbing, groping, beating, punching, and kicking their breasts, genitals and buttocks; stripping them of their clothes including in front of male detainees; conducting intrusive body searches; holding them naked for hours or days in detention, including in front of video cameras [to use as blackmail in the future] and in freezing conditions; forcibly cutting their hair; dragging them violently by their hair; and threatening to rape them and their female relatives. In the cases of men and boys, documented forms of sexual violence included agents threatening survivors and their relatives with rape; forcing them to undress; subjecting them to cold temperatures while naked; administering electric shocks to their genitals; sticking needles into their genitals; touching, pressing, kicking and beating their testicles and buttocks; and putting ice on their testicles for prolonged periods.24

At least seven protesters were executed, typically after cursory trials with no semblance of due process. The first of them, Mohsen Shekari, was hanged in prison on December 8, 2022, but that wasn’t public enough for the regime. Members of Parliament wanted a “lesson” pour encourager les autres. An unnamed police commander, quoted by Amnesty, said it would be “a heart-warming gesture towards the security forces.”25 A twenty-three year old wrestler, Majidreza Rahnavard, had the tragic misfortune to be selected as the “gesture.” I tell his story here (Premium Content—Paid subscribers only).

Not content to murder its own people, the Islamic Republic then went on to harass the families of the victims and prevent them from mourning their loved ones. As the one-year anniversary of the death of Mahsa approached, her father and an uncle were arrested to prevent a “traditional and religious ceremony” at her grave. Family members of murdered protesters were also detained.26 One family decided to hold a ceremony at home; security agents attended to intimidate the mourners and monitor the proceedings. Another family’s home was attacked by riot police firing tear gas.27

As I discussed in Part 1, the massive scale of the Woman, Life, Freedom protests, and the presence of a new generation of protesters in the vanguard—fearless and social media-savvy—brought hope that they would lead to genuine reform in Iran, and maybe even the overthrow of the Islamic Republic. Indeed, there were encouraging signs. The Morality Police had disappeared from the streets and according to the country’s prosecutor general, Mohammad Jafar Montazeri, they had been disbanded. Furthermore, he said, the law requiring the wearing of the hijab was under review.

But sadly, brutality works. Thanks to the regime’s savage response, the gargantuan demonstrations that shook the nation in the fall of 2022 started to peter out after the new year. By the summer of 2023, the Morality Police were back. And as for the hijab laws, they are in the process of being changed—to be more oppressive. A “Bill to Support the Culture of Chastity and Hijab,” which increases penalties for violations to up to ten years in prison, is making its way through the legislative process.28 No one speaks any longer about the imminent demise of the regime.

Still, opponents of the Islamic Republic are optimistic for the future. They note that despite the new law and the return of the Morality Police, the sight of women with their hair uncovered has now become common in the cities of Iran. Actress and activist Nazanin Boniadi estimates their numbers in the hundreds of thousands. “We're not seeing the same numbers [of demonstrators] on the streets,” she says. “But the revolution is very much alive in the hearts and the minds of the Iranian people. And Iranian society will never be the same again.”29

In the words of lawyer Shirin Ebadi, who in 2003 won the Nobel Peace Prize for her work in promoting democracy and human rights, “Look at it like a train. A train will get to its last station one day, but there are many stations that the train will stop at to let passengers out, let them in, or for many other reasons. I know that the last station is the toppling of the regime, and I know that we will get there.”30

One thing that has disappointed many opponents of the Islamic Republic, including Ebadi, is the weak response from the international community, including the United States under the Biden Administration. President Biden’s policy toward Iran in general, and the Woman, Life, Freedom protests in particular, will be the subject of the final installment in this series.

Michael Isenberg likes ribeyes, bourbon, and writing novels about Persia. Please check out his latest, The Thread of Reason, at http://amazon.com/dp/0985329750.

“Iran: Leaked documents reveal top-level orders to armed forces to ‘mercilessly confront’ protesters,” Amnesty International, September 30, 2022, downloaded November 28, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/09/iran-leaked-documents-reveal-top-level-orders-to-armed-forces-to-mercilessly-confront-protesters/.

Maryam Sinaee, “Authorities Try To Cover Up Another Teen Protester’s Death In Iran,” Iran International, October 7, 2022, downloaded November 28, 2023, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202210074997.

“Iran’s supreme leader breaks silence on protests, blames US,” Associated Press, October 3, 2022, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/iran-israel-middle-east-dubai-united-arab-emirates-25c14800b5b145d850fe3181eb062664.

Amnesty (2022), op. cit.

Krauss, Joseph, “EXPLAINER: Who is leading the crackdown on Iran’s protests?, Associated Press, October 13, 2022, downloaded December 18, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/iran-middle-east-577c596775fb9a78d78107004d29d0f9.

Jonathan Spyer, “Iran mobilizes proxies to fight growing protests,” The Jerusalem Post, September 30, 2022, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/iran-news/article-718537.

Pouya Ghorbani, “Iran protests: Victims shot in eyes hold on to hopes,” BBC, April 4, 2023, downloaded December 18, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64503873; Aida Ghajar, “Blinding As A Weapon (4): The Story Of The ‘Joker Of Tehran.’” Iran Wire, January 30, 2023, downloaded December 18, 2023, https://iranwire.com/en/news/113210-blinding-as-a-weapon-4-the-story-of-the-joker-of-tehran/; Mohammad Farzi, Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/joker.tehran_official/.

“Iran’s Security Forces ‘Systematically’ Targeting Protesters’ Faces,” Iran International, February 4, 2023, downloaded December 18, 2023, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202302040763.

Cora Engelbrecht, “Hundreds of Protesters in Iran Blinded by Metal Pellets and Rubber Bullets,” The New York Times, updated November 23, 2022, downloaded December 18, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/19/world/asia/iran-protesters-eye-injuries.html.

A second video, showing a woman tying her uncovered hair into a ponytail, and then marching toward a demonstration with her hand held up in the “Victory” gesture, was widely reported to be of Najafi, but turned out to be another woman.

Some reports say half an hour.

Parham Ghobadi, “Iran protests: Iran's Gen Z 'realise life can be lived differently',” BBC, October 13, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-63213745.

Farzad Saifikaran, (25 September 2022). "حدیث نجفی؛ «به پدرش فشار آوردند بگوید بر اثر مرگ مغزی مرده". Radio Zamaneh, September 25, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.radiozamaneh.com/732566/.

Parham Ghobadi, “Iran: Teen protester Nika Shakarami's body stolen, sources say,” BBC, October 4, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-63128510.

Saifikaran (2022), op. cit.

Masih Alinejad, X.com, September 29, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1575494887092686852.

“One Year Protest Report: At Least 551 Killed and 22 Suspicious Deaths,” Iran Human Rights, September 13, 2023, downloaded November 21, 2023, https://iranhr.net/en/articles/6200/.

Human Rights Activists News Agency, X.com, January 5, 2023, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://twitter.com/HRANA_English/status/1611137794658779137.

Parham Ghobadi, “Iran protests: Secret committee 'punished celebrities over dissent,'” BBC, April 25, 2023, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-65373847.

“Iran arrests a soccer player for criticizing government and insulting the soccer team,” Associated Press via NPR, November 24, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2022/11/24/1139162898/iran-arrests-soccer-player-voria-ghafouri-world-cup.

Artemis Moshtaghian, “More than a thousand protesters have been arrested in Iran. Here are three of their stories,” CNN, October 13, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/13/middleeast/profiles-arrested-protesters-iran-intl.

“Iran protester: 'They said if we didn't keep quiet, they would rape us,'” BBC, September 27, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-63047372.

Tamara Qiblawi, Barbara Arvanitidis, et al., “How Iran's security forces use rape to quell protests,” CNN, November 21, 2022, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2022/11/middleeast/iran-protests-sexual-assault/index.html.

Amnesty International, “They violently raped me”: Sexual violence weaponized to crush Iran’s “Woman Life Freedom,” December 6, 2023, downloaded December 19, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde13/7480/2023/en/.

“Mahsa Amini protests,” Wikipedia, updated November 21, 2023, downloaded November 21, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahsa_Amini_protests#Executions.

Fiona Nimoni, “Mahsa Amini: Protesters mark one year since death of Iranian student,” September 16, 2023, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-66834156; Farnaz Fassihi, “‘An Innocent and Ordinary Young Woman,’” The New York Times, updated September 17, 2023, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/16/world/middleeast/mahsa-amini-iran-protests-hijab-profile.html.

Parham Ghobadi, “Iran stops families marking anniversaries of protesters' deaths,” September 21, 2023, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-66879349.

The bill passed Parliament in September but was returned by the Guardian Council the following month due to “ambiguities.” “Iran: Compulsory veiling bill a despicable assault on rights of women and girls,” Amnesty International, September 21, 2023, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/09/iran-compulsory-veiling-bill-a-despicable-assault-on-rights-of-women-and-girls/; “Iran's Guardians Council Returns Hijab Law Due To 'Ambiguities,'” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, October 25, 2023, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/iran-hijab-law-guardians-council-ambiguities-return/32653783.html.

“What’s changed for women in Iran one year after Mahsa Amini’s death,” PBS, September 16, 2023, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/whats-changed-for-women-in-iran-one-year-after-mahsa-aminis-death.

Holly Dagres, “Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi: ‘If we don’t unite—we won’t be able to topple the Islamic Republic,’” Atlantic Council, September 20, 2023, downloaded December 28, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/shirin-ebadi-mahsa-amini-revolution-unite/.